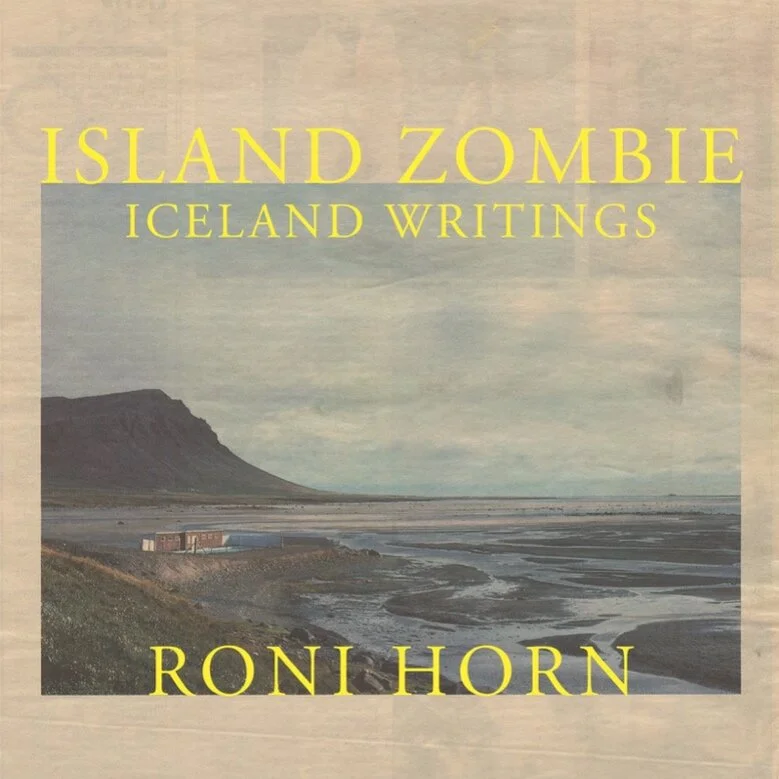

ISLAND ZOMBIE: ICELAND WRITINGS

by Roni Horn

Princeton University Press $35.00

Reviewed by Brendan Curtinrich

Imagine the planet’s barest beginnings: lava flows, sulfuric muck, the meanest scrub. Still young—only a couple dozen million years old—it’s a world of big weather and deep grottos, a landscape reenacted today on a freckle of land pinched between the molten core of Planet Earth and the freezing waters of the North Atlantic. This phantasmagoria of light and dark is the focus of Roni Horn’s new book, Island Zombie, a collection of visual and written art from her travels, largely by a red, two-stroke motorcycle, across Iceland.

At times quiet and at times chaotic, Island Zombie captures the incorporeality of a nation that embodies the evanescence of the northern lights and the ephemerality of fumarole vapor. Just as Iceland gives only intimations of itself to the viewer—reveals just as much by its volcanoes as it conceals with its eternal nights—so too does the book reveal some things outright while leaving others only suggested.

Horn’s spare prose is something akin to her own exploration of the island’s lava tunnels, those circuitous caves that are “filled with false starts, dead ends, and unknown exits” (33). While she ventures across a land obscured by tides and caverns, the reader is treated to a facsimile of that enigmatic journey by way of the words on the page. Resisting easy categorization, the book is an amalgamation of what might be called micro memories or flash contemplations, anomalous moments that assemble into a greater sense of the subject.

At one point Horn says, “A six-month solitary journey living in a tent is a long search for warmth” (57). Island Zombie is full of these simple profundities, and it is a treat to follow Horn’s mind across a landscape so austere and striking. Such a place seesaws between extremes and her writing captures this beautiful hostility, at once describing the winds racing from Miami to Reykjavík as “ferocious” and “criminal” and the island’s commonplace rainbows as “a sublime that’s lost its hold on brevity” (75).

It’s this transcendent wickedness that makes every moment Horn spends in Iceland exquisite, each one already a kind of unique dimension inhabited only by the person who lives it. In recalling one such memory Horn writes, “I see things unseen before, that is, things I’ve never seen before; and in their singularity and exact circumstance no one else has either. For instance—now in the small hours of the night a black cat strolls across the street below, a dark knot of something swinging from its jaw” (111).

These ideas of witness and seclusion are central to the collection. In a series of reflections borrowed from Icelanders, tales are told—understatedly—of people dying at sea, corpses lost to the waves or found later among the cliffs. The accounts are paired with calm, plain photos of the Icelandic landscape. Compositionally balanced, these emphasize both the tenuous harmony Icelanders have struck with their island’s fierce gales and the unadorned life the geography fosters.

As these other inhabitants join Horn’s narration (isolated for so much of the book up to that point), she reiterates the preciousness of emptiness and desolation. While you and I might not have much to do with Iceland, she is adamant that we still possess it in our minds. We stand to lose a refuge of imagination as our commercial and chemical habits squeeze isolation toward extinction. “Even if Timbuktu is blown into oblivion, Iceland, by virtue of its more resistant geology, can become a leading supplier of nowhere to the world . . . nowhere is a non-renewable resource, deeply vulnerable to overuse and inappropriate occupation,” she says (213).

In the end, the book is an artistic tribute to just that: the diminishing nowhereness of which Iceland, indistinct in its bleak high latitudes, so definitively represents. But a true island today? There can be no such thing. A world without exceptions corrupts all places, even those as fresh and immaterial as Iceland. As Horn eloquently warns, no nowhere, not even one whose molten, boiling maw orients us to the very core of earthly beginnings, is safe from becoming a zombie.

Brendan Curtinrich grew up on the north coast of Ohio and in the sheep pastures of New York. He studied creative writing at Hiram College and holds an MFA in Creative Writing and Environment from Iowa State University where he also served as the Nonfiction Editor and Book Review Manager for Flyway: Journal of Writing and Environment. He has walked long trails both in the U.S. and abroad, and writes nonfiction and fiction about ecological issues, particularly the ways human animals affect and are affected by the environment. His work has been published or is forthcoming in Trail Runner, Appalachia, Gigantic Sequins, Sierra, and Footnote.