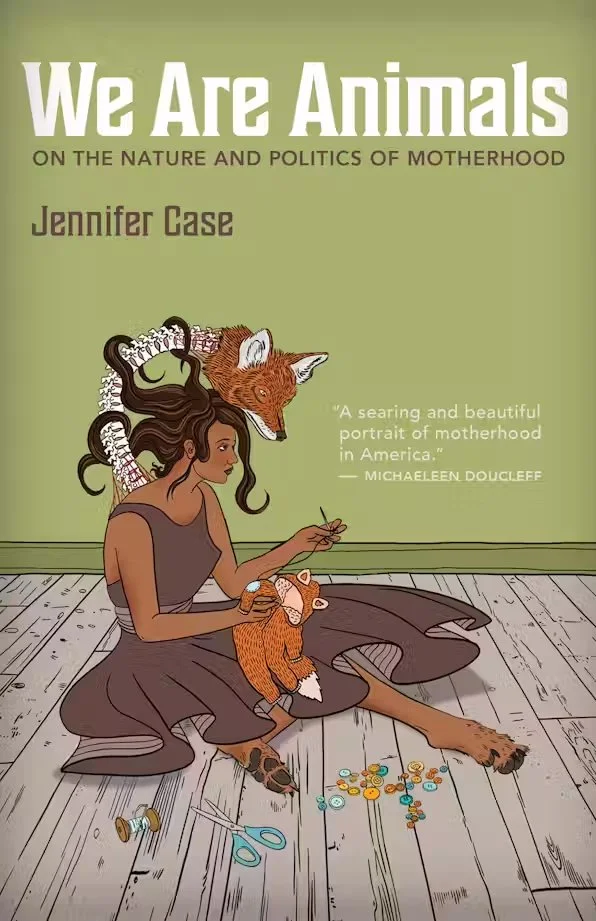

We Are Animals: On the Nature and Politics of Motherhood by Jennifer Case

Trinity University Press $19.95

Reviewed by Whitney (Walters) Jacobson

Since reviewing Jennifer Case’s first book, Sawbill: A Search For Place (University of New Mexico Press) in 2018, I have greatly admired her writing. So, when I read her unflinching essay, “A Political Pregnancy,” in The Rumpus in 2020 and electrifying “Message for the Animal Mother” in DIAGRAM in 2022, I had high hopes for Case’s next book. However, even having read those essays, I could not have anticipated the way We Are Animals: On the Nature and Politics of Motherhood (Trinity University Press, 2024) would cut to my core and affirm the contradictions, delights, and trials of motherhood in America.

We Are Animals consists of sixteen essays (including the prologue) that explore with honesty, accountability, and nuance the themes of motherhood, control, and birthing care. Case’s essays are both a balm for disheartened mothers and the uncomfortable, necessary pressure needed to staunch the United States’ propensity to dismiss, overrule, and disparage women’s experiences, needs, and desires.

To be quite frank, I didn’t inhale this book. I gulped it down, my body weeping with recognition and shuddering with validation. In rereading “Message for the Animal Mother,” it once again stunned me with its unreserved message and unabashed tone—the way it looked through my mask and said, “I see you, mother.” Yet, Case’s book perhaps most gutted me, demolishing every deflecting mirage I’ve constructed as self-preservation, when she revealed in her essay, “The Mother-Infant Dyad,”

When I was breastfeeding my daughter, I found myself—without necessarily intending it—nursing her to sleep for the first two years of her life. Though most parenting books and even my pediatrician told me not to . . . I did it because it was easy . . . because only in my arms, my body against hers, would she sleep longer than thirty minutes. (Case 166)

There was someone else who had done what I had done—something I did and enjoyed and felt was natural and yet hesitated to reveal due to stigmas. What a gift for Case to unconditionally reference such an intimate moment of valuing her instincts.

Even as Case advocates for mothers, she acknowledges her position and privilege as a white, heterosexual woman in the South in contrast to the challenges women of color, particularly Black women, face. She writes,

I need to be honest here. I am trying very hard not to make this about me. To not make this about the ways I did—and sometimes still do—ignore the harshness of the issue . . . I have told myself, other voices on race are more important. The voices of women of color are more important. I have told myself, no one needs to know about that moment in my bedroom, when I sat on the bed, and Nicolle knelt on the floor, scrubbing my afterbirth, and I realized this scene had been taking place for generations—very rarely were our roles reversed—and that I was complicit. . . . The truth: Black women die from childbirth three to four times as often as white women. I am a white woman. The numbers bear repeating. (Case 190-191)

Although she checks herself throughout the book, questioning her motives, biases, complicity, and blind spots, Case does so most explicitly in the essay “On Race and Motherhood in America” in which she reckons with her position in relation to her Black doula—four times referencing the moment of visible hierarchy in her home and many more times boldly revealing “the truth” about race that might otherwise be overlooked or obscured in America.

Perhaps, the greatest strength of We Are Animals is Case’s conviction in women. She resists the status quo in society and within herself when it does not serve female autonomy. In doing so, she grapples with defying norms she’s absorbed and reclaiming her instincts:

Because what I’m most interested in, after all, isn’t the perfect parent who wanted her children deeply and was enamored with every moment, but the woman who wasn’t always enamored yet who cared for and loved her children just the same. Hers, I believe, is the greater story of courage and love. She’s the woman who has something to teach me. The woman who I think has something to teach us all. (Case 140-141)

Ultimately, Case seeks to answer for women the question, “What choice have you ever had?” (49) and offer a hand filled with confidence and possibility: “You have always made the choices you needed to make. You are not stupid. And when the next choice comes, you will gather yourself—milk, bones, and bristle—and you will go” (3).

Whitney (Walters) Jacobson holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Minnesota State University Moorhead. Her poetry and creative nonfiction have been published in Punctuate, Feminine Collective, Up North Lit, After the Pause, and In the Words of Womyn International, among other publications. She is currently working on a collection of essays exploring skills, objects, and traits passed on (or not) from generation to generation. She maintains a curiosity in memoir and the themes of feminism, water, inheritance, blue-collar work, and grief.